Crosshairs on the grainy screen float to the right, latching onto the olive-green hulk lurking in a field beyond. The screen hazes for a moment with a "whoosh," and then resolves as the missile's rocket flickers away. Six seconds pass.

Boom.

Another Russian T-72 battle tank is out of action, many of its crew likely dead.

These aren't state-of-the art missiles, like the shoulder-fired Javelin. This is a Stugna-P, a less sophisticated anti-tank warhead made by Ukraine. A small group of soldiers can set up the missile on a tripod and wait for tanks to come into range. Using a remote control panel that looks like a hard camera case, an operator can paint the target with a laser until the missile strikes or allow its own laser-guidance to self-direct into the target.

It's proving quite effective. In three weeks of fighting, Russia has lost at least 270 tanks, according to the open source weapons tracking site Oryx — almost 10% of its estimated active force.

Ukraine's defense is proving so effective, in fact, that many analysts are attributing the failure of Russia's offense not only to its commanders, or to its tanks, but to the very idea of the tank itself, as a front-line weapon platform that can gain ground.

The emerging evidence of tanks' tactical weakness is "striking," as one expert put it, and it has opened up a debate about whether tanks might be on their way to joining chariots and mounted cavalry in the boneyard of military history.

Cheap, low-flying drones are striking tanks from above. Soldiers are using charred suburban landscape to ambush tanks with a new generation of fire-and-forget weapons that makes tank-killing unsettlingly simple, even in the hands of a volunteer.

"An infantry that is determined to fight is now super-empowered by having things like a huge number of point-and-shoot disposable anti-tank rockets," Edward Luttwak, a military strategist who consults for governments around the world, told Insider.

Tanks have ruled land warfare for more than 80 years. It's their job to punch through enemy positions so infantry can flood in and hold the newly gained ground. Tanks have long been susceptible to soldier-carried weapons like bazookas and recoilless rifles, as well as improvised explosives such as the anti-tank "sticky bombs" seen in the film "Saving Private Ryan."

Tanks are going to move, over time, into more of a mopping-up role.Paul Scharre, former US Army Ranger

But looking at the ineffectiveness of Russian tank attacks in Ukraine, one can see how technology — particularly advances in high explosives and guided missiles — is further tipping the odds to favor anti-tank defenders, to the point where tanks could arguably be rendered obsolete.

One defense analyst who spoke with Insider compared the role of tanks to that of the Swiss pikemen, Renaissance-era fighters armed with pikes and halberd who once were an army's frontlines.

This vanguard role, held then by foot soldiers and now by tanks, will likely shift to drones, robotic vehicles, and long-range strike systems.

"Tanks are going to move, over time, into more of a mopping-up role," said Paul Scharre, a former US Army Ranger and a director of studies at the Center for a New American Security.

'Point and shoot'

Shoulder-fired weapons are changing warfare.

With very little training, troops and even volunteers can defeat tanks. The Javelin is a fire-and-forget missile that allows its user to immediately move or take cover after firing. It has a mode to hit a tank where its armor is weakest: on top. Ukraine has been training its reservists, some of whom only recently joined, on these weapons since the war broke out.

The British- and Swedish-designed NLAW, or Next-generation Light Anti-tank Weapon, is also relatively simple to use. It weighs about as much as a case of beer. Balanced on a shoulder, an operator tracks a target within half a mile for a few seconds and then fires. The missile's fire-and-forget guidance system takes over.

"The weapon that makes a huge difference is these NLAWs, a light anti-tank weapon, the plastic tube with a hollow charge rocket," Luttwak said. "You point and shoot. A truck can drop 500 of them at the street corner in Kyiv."

And NLAWs are designed for exactly the kind of war Ukraine finds itself in.

"NLAW can attack from almost any position, from up high in a building to behind a tree or in a ditch," weapons manufacturer SAAB advertises on its website. "You can fire down 45 degrees and can shoot from inside a building, from a basement or from the second floor of a building out of the range of most tanks."

As the SAAB brochure implies, tanks are at their most vulnerable when in or approaching cities. Fighters can ambush them from around a corner, or fire from a window and slip away. These are known dangers to tanks but far beyond what they'd faced in World War II or Vietnam from the ground.

A century ago, the British conceived of tanks as land-going battleships, armored hulks that can traverse most terrain and surprise an enemy with an unmatched combination of speed and firepower. They were first deployed during World War I to break the stalemate of trench warfare.

Like battleships, they are fuel-guzzlers that pack a massive punch. A modern US M1A2 main battle tank weighs over 73 tons and fires a 120mm round. But even it, with its heavier-than-lead armor and missile jammers, is at risk near a city.

And the world is increasingly urban. By 2045, six billion people will be living in cities around the world, according to the World Bank, growing the city centers and suburban sprawls that armies must battle through.

Ukraine is exploiting the contours of its suburbs to negate Russia's advantages. Russia's advance on Kyiv stalled in the city's outlying suburbs, where determined fighters met their vehicle columns. The fighting has been block to block for weeks.

In Irpin, to Kyiv's northwest, Ukrainian artillery hammered armored vehicle columns that got within range, and small teams of troops and volunteers set up ambushes with anti-tank weapons. In Brovary, on Kyiv's east, a lieutenant told The New York Times that her teams set up anti-tank weapons along major highways and thoroughfares and lie in wait for them to come within the three-mile range of their Stugna-P missiles.

And then there's drones. They range from the size of fighter jets to the palm of a soldier's glove, and a technology scramble is underway to nullify them. But with so many makes and models, there's no one-size-fits-all way to jam, confuse, or destroy them.

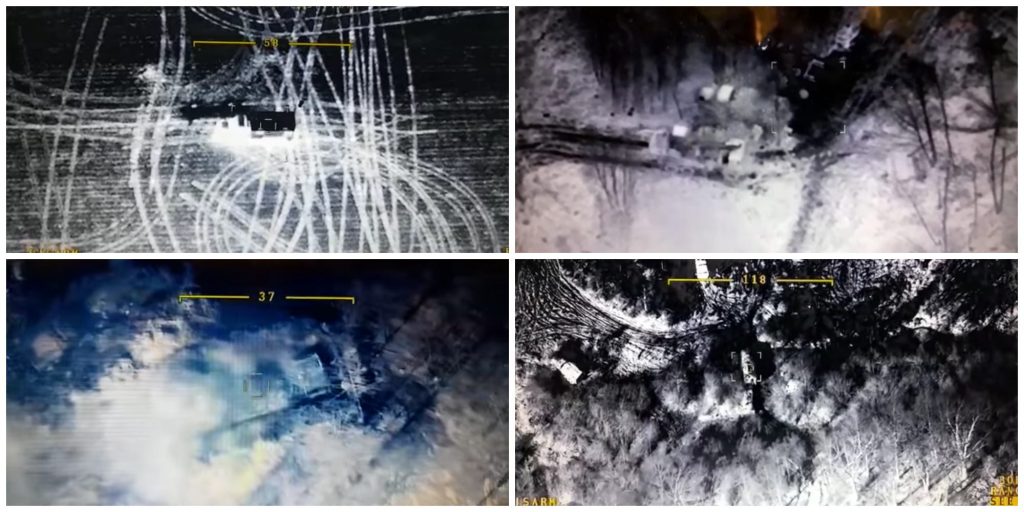

Combat in Ukraine has shown that drones offer big advantages. They can loiter close to armored vehicles and strike them with guided missiles, as the Turkish TB2 has shown again and again, or spot their positions to relay for artillery fire. The TB2 is like a poor man's MQ-9 Reaper, a drone the size of a Cessna aircraft that can loiter more than a day, fire up to four missiles or bombs, then return to base to be reloaded.

"We're actually seeing the Ukrainian military employ drones, the TB2 and smaller drones, to significant effect against Russian armored vehicles," said CNAS's Scharre. "Drones can be very effective in contested airspaces, in part because they can fly lower and in part because you're not risking a pilot."

Even smaller drones will also play a role. The Biden administration is sending 100 Switchblade drones to Ukraine, a single-use aerial vehicle the size of a backpack that can take out armored vehicles by kamikaze flying into them and detonating.

No way to run a war

Russian commanders have made bad decisions that have wasted their forces' potential. That includes tanks.

Soldiers, unsure of their ability to navigate through the mud, have been driving them down main roads. Russian tanks have been outrunning the infantry who can protect them.

With a range of around 600 miles, the T-72 weighs 40 tons and gets less than one mile per gallon. In Ukraine, many have strayed too far from the trucks they need to refuel; others have reportedly been sabotaged by their own crews. They have mostly stuck to streets, largely opting not to go off-road, disperse, or conceal their positions. In some instances, they've bunched together within range of artillery and paid a heavy cost.

Many Western analysts say they see few signs that Russia is capable of combined arms — where, for example, air power and artillery work in tandem to support the movements of tanks.

So tank proponents can rightly chalk up a lot of Russia's ruined tanks to terrible tactics, which means that the US's own tank-centric approach to land warfare is unlikely to change anytime soon.

From my distant vantage point, the Russian army appears to be incompetent in combined arms operations.retired Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster

Tanks have long been central to US Army doctrine against powerful rivals, and play a central part in Army lore.

It was the tanks of Patton's Third Army that helped to rescue the surrounded 101st Airborne in the Battle of the Bulge. And during the Gulf War, in 1991, US tanks routed Iraq's. In one encounter, a US group of nine tanks came upon a much larger Iraqi tank force and smashed through them in the Battle of 73 Easting in a classic tank clash.

"Mobile protected firepower will continue to be important to fighting and winning battles," said retired Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster, the commander of the Eagle tank troop at 73 Easting, who would go on to serve as national security adviser under President Donald Trump, in an email interview with Insider.

"No arm is decisive in close combat," McMaster continued. "To defeat a defending enemy in restrictive or urban terrain, commanders must integrate infantry with mobile protected firepower and fires from artillery or aircraft.

"From my distant vantage point, the Russian army appears to be incompetent in combined arms operations."

Still, guided munitions fired from ground and air are posing a massive challenge. Even tank proponents acknowledge that tanks must, like warships, become harder to kill via armor and defensive systems to confuse or intercept missiles.

One path, suggested the historian Jeremy Black in his 2020 book, "Tank Warfare," is to convert a battle tank into a drone mothership that can launch and control aerial drones or unmanned land vehicles.

Even armed with drones, tanks are still likely to be relegated to lesser roles as weaponry becomes more powerful and accurate.

When asked what a conventional clash between NATO and Russian forces might look like, Scharre said, "the ideal way to respond would not be necessarily to send tanks upfront," but rather to strike Russia's advancing armored vehicles with long-range artillery and missiles.

"Sure, armored vehicles would come but they're probably part of the second wave after we turned those armored columns into rubble."